Girls and Science a Review of Four Themes

Abstract

This forum paper dialogues with Crystal Morton and Demetrice Smith-Mutegi's Making "it" thing: Developing African American girls and young women's mathematics and science identities through informal Stalk learning. Their article unveils the experiences of participants in Girls Stem Institute, and how they challenged beliefs nearly their ability to perform in science and mathematics. I extend the discussion to explore the importance of access through community-based initiatives and stand on the premise that we will keep to oxygenate master narratives and perpetuate inequities if the structure and function of our programs neglect to claiming the status quo. Therefore, this newspaper serves equally a call to action to (1) recognize and accost spirit murdering from teachers and say-so figures who dismiss the abilities of Black girls to perform in Stalk; (2) create humanizing spaces within schools and the larger community for Black girls to access STEM with actuality; and (3) leverage the multidimensional identities of Black girls in ways that validate their cultural resources and brilliance. When nosotros commit ourselves to creating more equitable learning spaces in STEM, then our actions will marshal with our responsibleness to make Blackness girls matter.

Before I wasn't really confident in math or science and now afterwards the camp, when I started school, I was kind of confident about it. I knew kind of what to expect, not in geometry but in science. It increased a lot in scientific discipline. It increased in geometry as well only a lot in science after the campsite. ~Veronica

This forum paper dialogues with Crystal Morton and Demetrice Smith-Mutegi's (2022) Making "information technology" matter: Developing African American girls and immature women'southward mathematics and science identities through informal STEM learning. I shared an excerpt from Veronica, a participant in Girls STEM Institute (GSI)—the study'southward research context, whose self-efficacy in science and mathematics increased in response to her participation. Morton and Smith-Mutegi (2022) elevated the voices and experiences of Black girls in this informal STEM plan. Their phenomenological study explored the essence of the girls' experiences in the found, and how information technology shaped their self-efficacy in science and mathematics. This work is disquisitional because programs such equally GSI provide gateways for Blackness and Brown girls to enter into the Stalk disciplines, and counternarratives that disrupt essentialist views about them being too loud (Fordham 1993), ambitious (Esposito and Edwards 2018; Morris 2007), confrontational (Evans-Winters and Esposito 2010), hypersexual (Esposito and Dearest 2008), and unintelligent unless they are "acting white" (Fordham and Ogbu 1986).

If nosotros examine the culture of science and mathematics, negative narratives and stereotypes are fifty-fifty more pervasive and do non position girls of color as scientific or mathematical talent (Pringle et al. 2012), thus questioning their belongingness in Stem learning spaces (Olitsy et al. 2010). With increased initiatives and broadening participation efforts from the National Scientific discipline Foundation (NSF) and other federal organizations, numbers have remained steady over the years for populations who are underrepresented in the Stalk disciplines (NSF 2019). So, why aren't girls of color becoming women of color who pursue and persist in STEM careers? How can those obstructions exist mitigated for a more than promising hereafter? The aforementioned questions are rooted in structural and systemic issues that crave u.s.a. to interrogate the white heteronormative nature of schools in America. With Black girls losing involvement in scientific discipline and mathematics at younger ages, unquestionably we must accept a closer await at K-12 contexts within and across formal school settings.

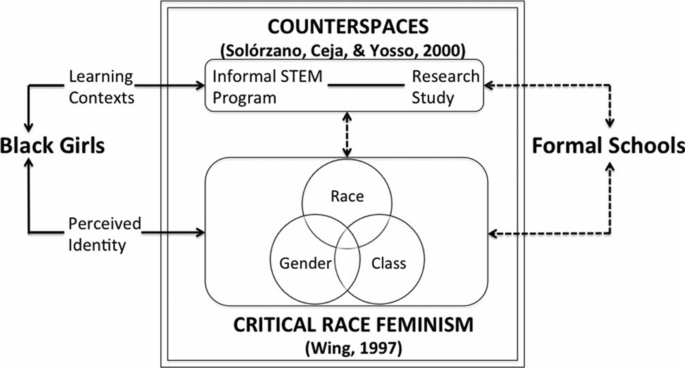

Drawing on Morton and Smith-Mutegi'southward (2022) study and my work related to leveraging community-based programs to promote access and equity in Stem (King 2017; King and Pringle 2019), I middle this newspaper effectually the post-obit three themes—our need to (i) recognize and address spirit murdering from teachers and authorisation figures who dismiss the abilities of Black girls to perform in Stalk; (2) create humanizing spaces within schools and the larger customs for Black girls to admission STEM with authenticity; and (3) leverage the multidimensional identities of Blackness girls in ways that validate their cultural resources and brilliance (Fig. one).

Multidimensionality of Black Girls' STEM Learning: A Conceptual Framework

Recognize and accost spirit murdering from teachers and dominance figures who dismiss the abilities of Black girls to perform in Stalk

Morton and Smith-Mutegi (2022) opened their newspaper with a quote from Anissa who shared an experience about her avant-garde honors science teacher stating, "Y'all practise know no college is going to accept y'all." Anissa revealed that her teacher's words broke her spirit; she depended upon her grandmother, aunts, and mother to help her believe again. Unfortunately, these experiences are not novel to Anissa and happen far too often to Black and Brown girls across this nation. Spirit murdering is defined as the "disregard for those whose lives qualitatively depend on our regard" (Williams 1987, p. 73). Bettina Beloved (2019a) describes spirit murdering as a boring decease steeped in racism whose intent is to reduce, humiliate, and ultimately destroy people of colour. Spirit murdering takes on many forms inside schoolhouse contexts such as a denial of protection, inclusion, or acceptance due to structures of racism that induce trauma and rob Blackness girls, like Anissa, of their dignity and humanity (Honey 2013; 2016). When their spirits are constantly under set on, it becomes increasingly difficult for them to learn.

Many teachers, administrators, and guidance counselors murder the spirits of Black girls every solar day without ever pulling a trigger. They injure Black girls through their perceptions, verbal utterances, and non-verbal body linguistic communication. Even if the initial aim of their actions was non to cause harm, the unintended consequences of their underlying racial and gendered innuendos cannot be ignored. Hines and Wilmot (2018) debate for the spirit healing of Black girls from "antiblack aggressions," where we take a closer look at their experiences in social and educational spaces. In the example presented past Morton and Smith-Mutegi'southward (2022), Anissa sought healing and restoration from matriarchs in her family. Love (2019b) refers to this equally the educational survival complex, which is exhausting because Black girls and their families are forced to navigate antidark spaces where their bodies, spirits, and existence do not matter. Nosotros must seek spirit healing for Black girls, which can only take place past first acknowledging the (un)intended trauma, attending to their physical and mental wellbeing, and so seeking to protect and accept them, in lieu of command tactics and rejection.

To truly recognize and overcome the spirit murdering of our most vulnerable populations, we must complicate race relations in schools and the greater American gild writ large. Rosa (2018) purports that the science education community cannot ignore and deny the impact of racism, which requires the utilize of intersectional approaches to inform our conceptions about STEM identity development. Stinson, Jett, and Williams (2013) call to examine our uses and misuses of school mathematics and how we can disrupt mathematics equally a White institutional infinite. Through disquisitional lenses and transdisciplinary approaches, we can interrogate the racialized and gendered science and mathematical experiences of Black girls in educational spaces.

The vignettes shared past Morton and Smith-Mutegi (2022) brilliantly brandish examples of when Black girls' abilities in scientific discipline and mathematics were dismissed. These kind of negative messages from teachers not simply induce spirit murdering, merely too have tangible outcomes that issue in their underrepresentation in the Stalk disciplines. Research suggests that Black girls who are high-achieving are typically disadvantaged past their teachers and school counselors who underestimate their potential and do not have high expectations for their academic success (Brickhouse et al. 2000; Brickhouse and Potter 2001). They rarely recommend Black girls for advanced courses and magnet programs, which result in them consistently being tracked into lower-level courses (Walker 2007). In these lower-tracked courses, classroom instruction typically emphasizes numeracy, literacy, examination grooming activities, and decontextualized skills (King and Pringle 2019; Lomax et al. 1995; Tate 2001). Therefore, even if Black girls are interested in the STEM disciplines, and practise well in their coursework, many are unable to compete with their White counterparts due to opportunity gaps (Carter and Welner, 2013; Ladson-Billings 2013; Milner 2010). Additional research reveals that Black girls are unfairly marginalized due to Discourses that only positively recognize those who are placidity, polite, passive, and fast workers (Wade-Jaimes and Schwartz 2019). Black girls are also targets of microaggression (Parsons et al. 2018), dysconscious racism (Male monarch 2015), and overdisciplining (Dear, 2019b) in formal school settings. We tin no longer afford to ignore the inherent racialized and gendered stereotypes that inform teachers' decisions to overlook the scientific discipline and mathematical abilities of Black girls (Else-Quest et al. 2013; Joseph et al. 2016). This leads to the next theme focused on humanizing STEM learning spaces and reconceptualizing the types of experiences that Blackness girls are afforded.

Create humanizing spaces inside schools and the larger community for Black girls to admission Stem with actuality

Morton and Smith-Mutegi (2022) discussed disparities in the types of learning experiences that Black girls are afforded, and advocated for transformative spaces where their abilities and belongingness in STEM are validated. In their argument, they centered the importance of self-efficacy (Bandura 1986; Britner and Pajares 2006) and teaching the Stem disciplines using socially transformative curricula to principal content, currency, context, critique, and bear (Mutegi 2011). William Tate (2001) argued that access to science and mathematics pedagogy in urban schools is a civil rights issue, and that inequalities in schooling have focused on sharing the same "educational infinite" with our White counterparts, rather than on admission to high-quality academic grooming. Our misguided energies within an American racialized order have produced caitiff opportunities for children of color to learn in transformative and culturally sustaining means. Therefore, school science and mathematics is a social justice issue that requires the states to rethink our spaces beyond the confines of formal schools to community-based and presumably more humanizing spaces.

Whiteness and Eurocentric ethics infiltrate the school curriculum and the ways in which science and mathematics are taught. We can leverage community-based spaces to contain and celebrate Afrocentric pedagogies, philosophies, and epistemologies for more than authentic ways of learning that embrace students' cultures and lived experiences. Programs like Girls STEM Institute are disquisitional for Blackness girls to build self-confidence and connectedness in STEM, while too maintaining their cultural competence. These spaces reposition Black girls as trouble solvers rather than the source of the problem.

In previous articles, I shared the experiences of fourth–eighth class Black girls who participated in I AM STEM Army camp—a comprehensive enrichment summer programme for which I am the founder and executive managing director. In I AM Stalk, we seek to develop culturally healthy students by meeting the needs of the whole child: heed, trunk, and spirit (Rex 2017; Ladson-Billings 1989). In reflecting on their Stem learning experiences, Black girls revealed that teachers who promoted their academic success formed positive relationships with their parents, were responsive to their needs, and encouraged critical and artistic thinking (Rex 2017). To gain an agreement of Black girls' STEM learning experiences across contexts, we documented the ways in which they translated their informal learning experiences into practice within their formal schools. When provided with equitable opportunities to larn, Black girls became agentic to go on their date in Stem activities throughout the school year. They identified field trips and engagement with accurate science phenomena as disquisitional components to igniting interests in Stem (Male monarch and Pringle 2019).

Unfortunately, many outreach programs are not particularly designed with girls of colour in mind. Therefore, programs like Girls Stalk Institute and I AM STEM are critical to moving the needle and irresolute the trajectory of Blackness girls and women in Stem. In guild to offer more humanizing spaces, nosotros must create programs where they are engaged in rigorous and relevant curriculum, and the organizers and instructors believe in and nurture their brilliance. We will continue to oxygenate master narratives and perpetuate inequities if the construction and office of our programs fail to claiming the status quo. Therefore, our conceptions of community-based programs should emphasize enrichment, validation, and whole-child development rather than remediation, credit restoration, and test preparation. It is our obligation to create transformative spaces for positive Stalk identity evolution and increased self-efficacy.

Leverage the multidimensional identities of Black girls in ways that validate their cultural resource and brilliance.

In this concluding theme, I applaud Crystal Morton and Demetrice Smith-Mutegi's efforts to organize and implement Girls STEM Institute, and telephone call for a shut examination of the circuitous identities of Black girls. Morton and Smith-Mutegi (2022) understand the importance of Black women scholars leveraging their resources to create community-based outreach programs that cover Black girls' multidimensional identities. They incorporated Stalk professionals who shared the same race and biological sex equally the camp participants, thus emphasizing the need for Black girls to run into Black women who are excelling in Stem careers so they can project themselves into that epitome (Britner and Pajares 2006; Rex and Pringle 2019). Only put, representation matters! A synthesis of research examining the intersectional experiences of Black women and girls in STEM pedagogy revealed that Black girls have distinct experiences due to their social identities, psychological processes, and educational outcomes (Ireland et al. 2018). This review discovered that many studies have not best-selling the key psychological processes associated with identity nor the simultaneous racialized and gendered experiences in Stem educational settings.

To address these gaps in the literature, my colleague and I adult a conceptual framework exploring the Multidimensionality of Black Girls' STEM Learning (King and Pringle, 2019). It acknowledges the complex interactions of their perceived identities within and across educational contexts by connecting Solorzano, Ceja, and Yosso'southward (2000) counterspaces with Fly's (1997) critical race feminism (CRF).

CRF focuses on the lived experiences of those who face multiple discrimination based on race, gender, and class, and how those factors intersect in complex means within a system of White male patriarchy and racist oppression (Fly 1997). CRF is a multidisciplinary arroyo that emphasizes both theory and do and encourages activity on micro and macro levels to improve the plight of Black women and girls. Counterspaces are places where deficit notions of people of color can exist challenged and replaced with a positive and affirming climate. These spaces can be concrete, conceptual, or ideological and are fostered through positive support systems, which include family, friends, community members, and organizations. Counterspaces provide opportunities for Black girls to problematize deficit notions, establish and maintain relationships, and validate each other's experiences as of import knowledge (Solórzano et al. 2000; Solórzano and Villalpando 1998).

Four Black center and high school girls who participated in GSI described the enrichment program as a identify of comfort where they felt safety taking risks and being their accurate selves. Participants' accounts provided more nuanced understandings nigh rubber and comfort. In designing programs, organizers should annotation that Black girls capeesh environments where they can try and fail, answer and be incorrect, and provide naïve solutions to problems as they work toward more sophisticated understandings. In these spaces, they tin can ask for help, clarification, and additional time to process without their intelligence existence misinterpreted or misjudged. Furthermore, many Blackness girls value collaboration and fostering a customs of learners over contest.

Utilizing the Multidimensionality of Black Girls' Stalk Learning conceptual framework equally a lens to respond to the study, GSI served as a counterspace. Participants discussed the transferability of the science and mathematics skills learned during the institute to their formal school curriculum and attributed their increased conviction to the rich experiences that were afforded. Activities similar the financial simulation and seed dissections provided admission to science and mathematics concepts that were applicable to their lives. The authors' careful and intentional design of the constitute (inclusive of socially transformative STEM curriculum), and the girls' rich depictions of its impact on their self-efficacy, conviction, and overall identities, made GSI a counterspace. Morton and Smith-Mutegi (2022) leveraged their social capital letter by connecting content to Black girls' interests and cultures and then that the curriculum was rigorous and relevant. They related to the girls, were embedded in their customs, and shared like aspects of their identities.

Other scholars have used intersectional approaches to amplify and certificate the stories of Black children in breezy contexts. For example, Mark (2018) employed an intersectional lens to conduct a longitudinal case study exploring the experiences of a Black male who engaged in a community-based Stem program focused on social justice and its impact on his STEM identity development. Gholdy Muhammad (2014) discussed the benefits of a summertime writing collaborative that she developed specifically for Black adolescent girls to understand their "…self-identity among ascendant narratives that attempt to 'write' Black girls realities" (p. 323). Her nowadays-twenty-four hours literary society provided a counterspace for Black girls to negotiate, mediate, and construct their identities. These spaces often serve as a mechanism to validate the cultural resources and luminescence of Black children in ways that traditional schools exercise not. This is consequent with recommendations from Lemons-Smith (2013) who states that Black children bring personal and intellectual capital letter from out-of-school programs that must be leveraged in formal schoolhouse settings.

Final thoughts

Morton and Smith-Mutegi (2022) titled their paper "Making 'it' matter." In this connected dialogue, I highlight our urgency to make "Black girls affair" in Stalk education. In science education specifically, we often drag content over context, and being correct over being morally just. This paper is a call to humanize science by prioritizing mattering over matter. When we teach the fundamental principles of our discipline, children are required to learn that "matter" is anything that has mass and takes up space. This concept informs every branch of science with implications ranging from the particulate to astronomical aspects of our field. What if we reconceptualized the construct of affair in Stalk learning spaces to include the wellbeing of all children? Love (2019b) described mattering every bit a quest for humanity, an internal want for liberty, joy, and restorative justice. Nosotros must transform science and mathematics learning spaces so that Blackness girls can experience spirit healing in lieu of spirit murdering, humanizing educational experiences over those that are oppressive, and their multidimensional identities being validated rather than critiqued and ignored.

Previously, I discussed the importance of familial matriarchs who assist Blackness girls to heal from spirit murdering to survive, persist, and maintain their overall sanity in Stalk learning spaces—spaces that are often violent and unwelcoming. Nosotros must extend their village to include community matriarchs and othermothers who volition presume a sense of responsibleness to honey and nurture Black girls as if they were their own biological children (Instance 1997; Foster 1993). May we carefully consider the roles that we choose to play and serve equally mentors, teachers, coconspirators, listeners, part models, and friends. I close this paper with some other quote from Veronica who stated, "…I used to call up I wasn't cute. The military camp kind of showed me that you are beautiful in your own way." When nosotros create more equitable spaces for Blackness girls in STEM, they will begin to internalize their dazzler and realize that not just do they belong here, but they besides matter!

References

-

Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive telescopic of self-efficacy theory. Journal of social and clinical psychology, 4(three), 359–373.

-

Brickhouse, N. W., Lowery, P., & Schultz, K. (2000). What kind of a girl does science? The construction of school science identities. Journal of Research in Science Education, 37, 441–458.

-

Brickhouse, N. Due west., & Potter, J. T. (2001). Young women'south scientific identity formation in an urban context. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38, 965–980.

-

Britner, Due south. Fifty., & Pajares, F. (2006). Sources of science self-efficacy beliefs of middle schoolhouse students. Journal of Enquiry in Science Teaching: The Official Journal of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, 43(v), 485–499.

-

Carter, P. L., & Welner, K. M. (Eds.). (2013). Closing the opportunity gap: What America must practice to requite every child an even risk. Oxford University Press

-

Case, K. I. (1997). African American othermothering in the urban uncomplicated school. The Urban Review, 29(1), 25–39.

-

Else-Quest, Northward. M., Mineo, C. C., & Higgins, A. (2013). Math and science attitudes and accomplishment at the intersection of gender and ethnicity. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(3), 293–309.

-

Esposito, J., & Edwards, East. B. (2018). When Black girls fight: Interrogating, interrupting, and (re) imagining unsafe scripts of femininity in urban classrooms. Didactics and urban order, 50(i), 87–107.

-

Esposito, J., & Love, B. (2008). More a video hoe: Hip hop as a site of sex activity teaching about girls' sexual desires. The corporate assault on youth: Commercialism, exploitation, and the end of innocence, 43–82.

-

Evans-Winters, Five. E., & Esposito, J. (2010). Other people's daughters: Critical race feminism and Black girls' education. The Journal of Educational Foundations, 24(1/ii), eleven.

-

Fordham, Southward. (1993). "Those loud Black girls":(Black) women, silence, and gender "passing" in the academy. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 24(1), 3–32.

-

Fordham, Due south., & Ogbu, J. U. (1986). Black students' school success: Coping with the "burden of 'acting white.'" The urban review, 18(3), 176–206.

-

Foster, Yard. L. (1993). Othermothers: Exploring the educational philosophy of Black American women teachers. Feminism and social justice in education: International perspectives, 101–123.

-

Hines, D. E., & Wilmot, J. M. (2018). From spirit-murdering to spirit-healing: Addressing anti-black aggressions and the inhumane discipline of Black children. Multicultural Perspectives, 20(2), 62–69.

-

Republic of ireland, D. T., Freeman, 1000. Due east., Winston-Proctor, C. E., DeLaine, Thou. D., McDonald Lowe, S., & Woodson, K. M. (2018). (Un)subconscious figures: A synthesis of research examining the intersectional experiences of black women and girls in STEM teaching. Review of Research in Education, 42(1), 226–254.

-

Joseph, Due north. M., Viesca, K. M., & Bianco, M. (2016). Black female adolescents and racism in schools: Experiences in a colorblind society. The High School Journal, 100(1), 4–25.

-

King, J. Due east. (2015). Dysconscious racism: Ideology, identity, and the miseducation of teachers. In Dysconscious Racism, Afrocentric Praxis, and Education for Human Freedom: Through the Years I Go on on Toiling (pp. 125–139). Routledge.

-

Rex, N. S. (2017). When teachers go information technology right: Voices of blackness girls' informal Stalk learning experiences. Journal of Multicultural Affairs, 2(1), v.

-

Male monarch, North. S., & Pringle, R. Thou. (2019). Black girls speak STEM: Counterstories of informal and formal learning experiences. Periodical of Inquiry in Science Educational activity, 56(5), 539–569.

-

Ladson-Billings, One thousand. (1989). A tale of ii teachers: Exemplars of successful pedagogy for Black students. Paper presented at the Educational Equality Project Colloquium, New York, NY.

-

Ladson-Billings, G. (2013). Lack of achievement or loss of opportunity. Closing the opportunity gap: What America must do to requite every child an even chance, 11.

-

Lemons-Smith, S. (2013). Tapping into the intellectual capital of Black children in mathematics: Examining the practices of pre-service elementary teachers. In J. Leonard & D. B. Martin (Eds.), The brilliance of Black children in mathematics: Across the numbers and toward new soapbox (pp. 323–339). Data Age Publishing.

-

Lomax, R. G., West, M. M., Harmon, Grand. C., Viator, G. A., & Madaus, Thousand. F. (1995). The bear on of mandated standardized testing on minority students. Journal of Negro Instruction, 171–185.

-

Love, B. Fifty. (2013). "I run across Trayvon Martin": What teachers tin can learn from the tragic expiry of a young black male. The Urban Review, 45(3), 1–15.

-

Love, B. L. (2016). Anti-Blackness state violence, classroom edition: The spirit murdering of Black children. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching, 13(1), 22–25.

-

Dearest, B. L. (2019). The spirit murdering of Blackness and Brown children. Education Week, 38(35), 18–xix.

-

Honey, B. 50. (2019b). Nosotros desire to practice more than than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

-

Mark, S. L. (2018). A bit of both science and economics: A non-traditional Stem identity narrative. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 13(four), 983–1003.

-

Milner, H. R. (2010). Start where you are, but don't stay there. Harvard.

-

Morris, E. Westward. (2007). "Ladies" or "loudies"? perceptions and experiences of Blackness girls in classrooms. Youth & Society, 38(4), 490–515.

-

Morton C. & Smith-Mutegi (D) (2022). Making "it" affair: Developing African American girls and young women'southward mathematics and science identities through breezy STEM learning. Cultural Studies of Science Pedagogy, 1–20.

-

Muhammad, Thousand. G. (2014). Focus on Middle Schoolhouse: Black Girls Write!: Literary Benefits of a Summer Writing Collaborative Grounded in History: Detra Price-Dennis. Editor. Childhood Educational activity, ninety(4), 323–326.

-

Mutegi, J. West. (2011). The inadequacies of "Science for All" and the necessity and nature of a socially transformative curriculum arroyo for African American scientific discipline didactics. Journal of Research in Science Education, 48(3), 301–316.

-

National Science Foundation, National Center for Scientific discipline and Engineering Statistics. (2019). Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Technology: 2019. Special Study NSF 19–304. Alexandria, VA. Available at https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf19304/

-

Olitsky, Southward., Flohr, 50. L., Gardner, J., & Billups, M. (2010). Coherence, contradiction, and the development of school science identities. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 47(10), 1209–1228.

-

Parsons, E. R., Bulls, D. L., Freeman, T. B., Butler, K. B., & Atwater, M. M. (2018). Full general experiences+ race+ racism= Work lives of Black faculty in postsecondary science education. Cultural Studies of Scientific discipline Pedagogy, 13(2), 371–394.

-

Pringle, R. M., Brkich, M. M., Adams, T. L., West-Olatunii, C., & Archer, D. A. B. (2012). Factors influencing elementary teachers' Positioning of African American girls as science and mathematics learners. Schoolhouse Scientific discipline and Mathematics, 112(iv), 217–229.

-

Rosa, K. (2018). Science identity possibilities: A look into Blackness, masculinities, and economic ability relations. Cultural Studies of Science Education, xiii(iv), 1005–1013.

-

Solórzano, D. G., & Villalpando, O. (1998). Critical race theory, marginality, and the experience of students of color in college education. Sociology of Education: Emerging Perspectives, 21, 211–222.

-

Solórzano, D., Ceja, Thou., & Yosso, T. (2000). Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate: The experiences of African American college students. Journal of Negro Educational activity, 60–73.

-

Stinson, D. W., Jett, C. C., & Williams, B. A. (2013). Counterstories from mathematically successful African American male person students: Implications for mathematics teachers and instructor educators. The brilliance of Black children in mathematics: Across the numbers and toward new discourse, 221–245.

-

Tate, W. (2001). Science education as a ceremonious right: Urban schools and opportunity-to-larn considerations. Journal of Enquiry in Scientific discipline Pedagogy: The Official Periodical of the National Association for Research in Science Didactics, 38(9), 1015–1028.

-

Wade-Jaimes, K., & Schwartz, R. (2019). "I don't think it's science:" African American girls and the figured world of school science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 56(6), 679–706.

-

Walker, Due east. N. (2007). Why aren't more than minorities taking avant-garde math? Educational Leadership, 65(3), 48.

-

Williams, P. (1987). Spirit-murdering the messenger: The discourse of fingerpointing as the law'southward response to racism. U. Miami L. Rev., 42, 127.

-

Wing, A. K. (1997). Disquisitional race feminism: A reader. New York University Press.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This manuscript is part of the special event "Science pedagogy and the African Diaspora in the United States," invitee edited by Mary M. Atwater and Jomo Due west. Mutegi.

This review essay addresses issues raised in Crystal Morton and Demetrice Smith-Mutegi'paper entitled: Making "it" matter: developing African American girls and young women's mathematics and science identities through informal STEM learning (https://doi.org/x.1007/s11422-022-10105-8)

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits utilise, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long equally yous give appropriate credit to the original writer(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and bespeak if changes were fabricated. The images or other tertiary political party material in this article are included in the article'southward Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the textile. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, yous will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Male monarch, N.South. Blackness girls thing: A critical assay of educational spaces and phone call for community-based programs. Cult Stud of Sci Educ 17, 53–61 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-022-10113-8

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-022-10113-8

Keywords

- Black girls

- Identity

- Informal learning

- STEM

- Community

- Intersectionality

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11422-022-10113-8

0 Response to "Girls and Science a Review of Four Themes"

Postar um comentário